Day by Jay #6: What new normal?!

🎨 NYC 📊 The force of friction 🧘♀️ Comfort zone

Welcome to “Day by Jay!” A combination of topics I find interesting and enjoyable, I hope you do as well. You can find previous editions here. Please let me know what you think @jaydimonte.

🎨Art

I drew this picture of New York when it was a consistent feature of front-page news, sometime in April or May.

May feels like ages ago.

This month we are protesting, addressing, and, yes, politicizing systemic racism.

In the midst of a national movement and a pandemic, “What will be the new normal?” is a more important question now than ever.

📊VC & etc.

Predictions for the "new normal" are a dime a dozen. A few weeks ago, they were nothing but hypotheses. Now as states reopen, we're getting a preview of what the future might look like. But, it's not yet clear.

Official policy is one thing, it changes instantly. Societal norms and individual tolerances are another, adjusting over time. For example, outdoor dining is available in 44 of 50 states. Only 40% of respondents have patronized a restaurant.

At one point, I described how VCs approach industries affected by COVID. One prevailing question was, “How do we know if this uptick/downturn is permanent? How long does it last?”

Physics gives us the answer.

Force of Friction

fric·tion /ˈfrikSH(ə)n/

(noun) The resistance that one surface or object encounters when moving over another.

(noun) Conflict or animosity caused by a clash of wills, temperaments, or opinions.

COVID created a lot of friction and continues to do so. Look no further than teachers and parents launching school-from-home. It was not a smooth transition.

In physics, the force of friction resists another force pushing against an object:

If the surface is rough or sticky, friction is high. If the object is big and heavy, friction high. When friction is high, there is a lot of resistance to change.

We should look at stickiness and bigness to explain how we reacted to COVID pressures. We can look at them to understand which adaptations and changes are lasting.

Mass: How big?

Bigger things are harder to move. There’s more friction creating resistance.

❕For example: Remote work.

My firm of 11 transitioned quickly. A few of us didn't come in one day, then the rest stayed home the next.

My fiance's firm of 100-200x that first came up with a work remote plan, tested that plan in shifts, assessed where the system faltered, fixed those issues, then decided to work remotely. How with firm size determine when (or if) we go back to the office?

❔To consider: Small entities will move first and give us a glimpse of what the larger entities will eventually do. (Small may also apply to the homogeneity of a group.) Leading indicators include:

Sum of parts: What are individuals doing? E.g. Have families begun dining out? Before the sales orgs' wining-and-dining resumes, individuals must begin visiting restaurants

New units: What do newly built or formed entities look like? These are the most nimble groups since they are not encumbered by mass. They have fewer stakeholders and no baggage of inertia. E.g. are new startups hiring in their own city or are they building distributed teams?

The early adopters: What are the early adopters doing? Particularly, the early adopters that are well respected in their cohorts? E.g. Facebook and Twitter were the first to go remote and then to declare "no earlier than" dates for resuming work. How will laggards follow their lead in resuming office work?

Coefficient of Friction: How sticky?

The higher a surface's “coefficient of friction” is, the stickier that surface or system is. Some environments are stickier than others.

It’s much easier to fire a 1099'd gig worker than a contractor operating under an SOW. It’s most difficult to fire an employee.

❕For example: Physical health.

Over 50% of those surveyed noted they are exercising more in quarantine. 2/3rds of those people said its because they have more time! Getting rid of commutes lowered a lot of the friction to exercise. Will those people continue to exercise at the same level once we start commuting again?

We see this again in grocery. A quarter of respondents started grocery delivery during COVID. The added requirements for shopping (masks, waiting in line, overcoming discomfort) raised friction associated with shopping. Once these barriers disappear, will grocery delivery volume continue?

❔To consider: Friction works both ways. Many times, when there is resistance to adopt an initiative, there is later resistance to give it up! We should think about where that resistance is coming from to understand how permanent it is:

Fundamental attribution error: How much is the new behavior driven by a temporary set of defaults, incentives, or other environmental factors? The friction holding us in a new place may not always be there. E.g. while working remotely, it is harder to have "water cooler" conversations. We adopted slack to fill this gap. Let’s say we go back to the office during COVID, but work out of separate conference rooms. If we can shout between offices, will our use of slack continue?

Staying power: Is the new behavior very sticky because of network effects or high switching costs? E.g. We have adopted slack, did we make it extra sticky by getting our whole team using it? By integrating into our CRM, video system, social media? Will giving it up feel like a step backward?

Behavioral psychology: Individual humans are particularly subject to their environments. The least sticky systems require willpower. Are we forcing the behavior or has it become a natural part of our day?

E.g. With remote work, communication is purposeful.

For some of us millennials, picking up the phone might not feel natural. It takes willpower and might not happen.

Once we start calling and make it a habit, calls are more likely to happen.

If we set a recurring check-in call on the calendar, it becomes a default. The phone call always happens.

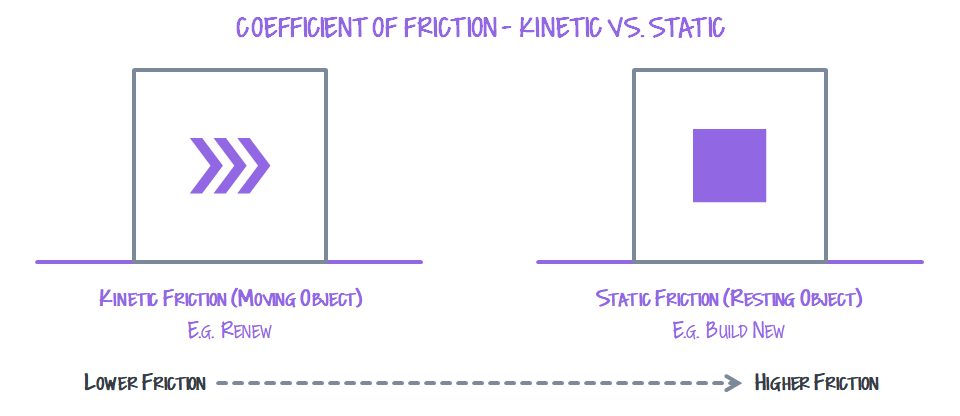

Kinetic or static: Already moving?

The coefficient of friction is not only dependent on how sticky a surface is. It's also dependent on if an object is moving or still. It’s easier to keep an object moving than it is to get an object to move in the first place.

It's very clear to see this when considering virality:

It’s harder to create a meme than share one.

It’s harder to build a budget than renew one.

It’s harder to win a contract than expand one.

❕Example: Video conferencing.

If you had already started to use Zoom for a few meetings, it was easy to expand its use. If your work was dependent on in-person interaction, it was difficult to adjust to virtual. For example, online teaching or coaching. You had to learn new instruction styles, technology, ways to engage your audience. Once we can be back in person, will we continue to use video infrastructure?

❔To consider: We entered a virtual world. Where will we come out of it? Think about why we're using new tools:

Discover: Is this new behavior one we only discovered because of COVID? The first time you buy something, there is a high level of friction. You have many questions - will it work? Is it worth it? There is much less friction with the second sale. E.g. you discover a new product after spending more time on Instagram. Their COVID-introduced sale prompted you to buy where you might not have before. Now you are hooked!

Unblock: Is this new behavior one that was only allowed because of COVID? E.g. Once we allowed telemedicine across state borders, its unlikely the regulation comes back.

Accelerate: Was something moving before but is moving faster now? COVID may have brought us to the tipping point. E.g. consider Zoom. With almost universal adoption of Zoom, its much easier to talk to my grandparents now.

Acceleration

When two forces act upon an object, and one of those forces is stronger, it will cause the object to not just move, but accelerate.

If the force of COVID is greater than friction, we will see the acceleration of trends kicked off by COVID.

Friction is a product of how "massive" and complex an object is and how "sticky" the environment. Using this framework, we can anticipate what trends may accelerate with COVID. Additionally, trends that accelerate to a tipping point will be more likely to stick.

On an episode of Pivot, Scott Galloway said something along these lines. COVID is an accelerant of emerging trends. If you look at where your business could be 10 years from now, think about that your business being there next year.

We see this in the rise of home offices, distributed teams, the "rise of the rest." We see this in the adoption of telemedicine and other therapies. We see this in grocery delivery and retail pickup.

Is COVID enough to push these trends into the new normal?

🧘♀️Deep Breath

It’s only after you’ve stepped outside your comfort zone that you begin to change, grow, and transform — Roy T. Bennett

Up to today, many of us have been unwilling to step outside our comfort zones. We haven't acknowledged how we live in an imperfect and unfair society. We didn't take action or ownership, we didn’t speak out because it was outside our comfort zone.

I hope our “new normal” comes with more learning, listening, discussion and action. If we step outside our comfort zone enough, it eventually expands.

A reminder from last issue, information on Black Lives Matter can be found here.

Thanks for reading, please let me know what you think. Stay safe and healthy. Ciao! 👋