Day by Jay #8: The F-word

🎨 Ponte di Rialto 📊 Invest in fragmentation 🧘♀️ Goldfish

Fragmentation is everywhere and has only accelerated with the onset of the pandemic.

City-dwellers ditched dense metros, opting for sprawling suburbs and rural towns. Cycle-enthusiasts stopped congregating at Flywheel, instead hopping on Peletons at home. Students returned from summer to downsized or closed classrooms, many now studying with siblings at home.

Fragmentation & Consolidation

There are “only two ways to make money in business: One is to bundle; the other is unbundle.” — Jim Barksdale, CEO, Netscape

Most startups unbundle existing products and markets. This is fragmentation. When startups undergo M&A it's generally to bundle products and services. This is consolidation.

VCs make money on this cycle in a very specific way. We invest in fragmentation and exit into consolidation.

Markets go through cycles of fragmentation and consolidation. Whether a market consolidates or fragments is dependent on environmental changes. These may be consumer preference changes, macroeconomic events, or new technology innovation.

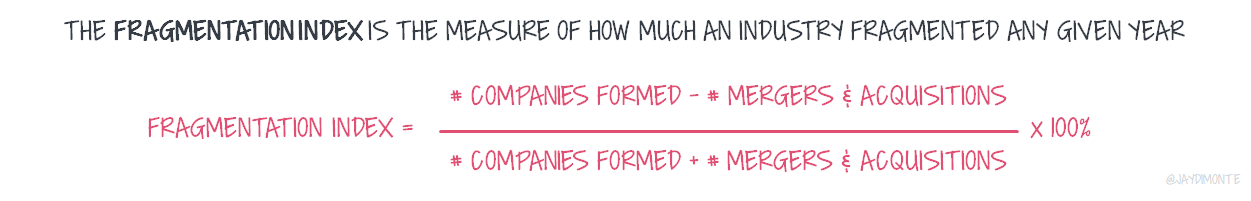

We can infer where an industry is in the fragmentation/consolidation cycle by using a fragmentation index. I’ve defined a fragmentation index that compares how many new companies form and existing companies merge each year:

When the index is positive, the market is fragmenting. When it’s negative, the market is consolidating. The larger the absolute value of the index is, the stronger the fragmentation or consolidation trend is.

Ex 1: SaaS market oscillates

SaaS (software-as-a-service) emerged in the late 90s. At the time, most software was hosted on-premise and customers were slow to transition. They didn't trust "the cloud." They thought their data was safer behind the corporate firewall. Also, SaaS companies still had to buy and maintain hardware on behalf of their customers. Starting a company and selling your services wasn't any easier than before. Even so, the market began to grow and fragment.

The dot-com bust in 2001 drove the market to consolidate. Presumably, with fewer sources of capital, companies had little choice but to sell.

The global financial crisis further tightened capital markets not to mention customers' budgets. 2007-08 marked peak consolidation.

But then, the emergence of cheap cloud service providers changed the game. Amazon's AWS launched in 2006, Microsoft's Azure in 2010, and Google Cloud in 2011. It became much easier and cheaper to start a SaaS company and so many, many did!

Of late, it seems as if we are trending back into consolidation territory. Of course, it could be that more recent data lacks completeness. (Pitchbook backfills data when transactions are announced so new companies may have a delay in reporting.) But it could also be that fewer SaaS companies are being formed. We know that more capital has been going into fewer companies since 2015. At the same time, public companies' stock prices are at all-time highs and balance sheets flush. The situation makes startup acquisitions attractive options.

Ex 2: eCommerce fragments

In the example above, the emergence of cloud infrastructure accelerated fragmentation. Well developed infrastructure is necessary to power market fragmentation. Another great example is e-commerce.

New market fragmentation & old market consolidation

eCommerce is on a tear. In 2012, only 8% of retail was online. By 2019, 16% was. This year? Almost 30% of all retail transactions happened online. That's ample opportunity for eTailers.

With a market growing so fast, it should come as no surprise that there has never been a period of consolidation. Even as acquisitions picked up, new company creation exploded and fragmentation continued.

Compare that to the department store market. The 1990s were peak in-person retail. Over time growth slowed and consolidation ramped. (Also, godspeed to the folks launching a department store in 2020.)

What happened? Of course, it’s easier to click a button than drive to the store. But, there is more to it than that.

Fragmentation enablers

Before Amazon, buying something online sucked. You didn't know if your credit card was safe. You didn't know the quality of goods you bought. You didn't know when, or even if, they would show up!

Amazon solved the problem. They built the "full stack," integrating everything from product search to payments to delivery. With this full stack came a seamless customer experience. Once consumers got a taste of it, they wanted more!

Demand for eCommerce unlocked.

Still, becoming an eCommerce company was hard. There were big upfront development costs and new supply chains to manage. eCommerce needed to solve those problems to flourish.

Platform companies emerged and established the eCommerce infrastructure we know today. They solved problems up and down the supply chain, for example:

Setup and operation: Shopify and WooCommerce let anyone create an online storefront

Production: Overlo and Printify popularize drop shipping and easy product sourcing

Distribution: Shipbob and others store, pick, pack, and ship products

Transaction/Payments: Stripe and Braintree make payments simple and trustworthy

Acquisition: Social media, largely YouTube and Instagram, make reaching and acquiring customers easier

Because it required so much capital to set up and operate an eCommerce business in the early days, only those serving the biggest markets constituted an investment. Once infrastructure players took on the heavy lifting, starting a business became cheap and easy. Companies could afford to serve niche markets. You didn’t need to be an engineer to build a site. You didn’t need to know logistics to deliver product. Anyone with a credit card could start an eCommerce business. And they did! The eCommerce market has exploded and fragmented. There are over seven million online retailers globally.

Fragmentation. Invest early and often.

This cycle happens every time a new market emerges. The first entrant unlocks demand. Other entrepreneurs, recognizing the roadblocks that keep supply from meeting demand, build infrastructure. With lower costs and expertise, new entrants flock to the market. They serve more and more niche markets and the market fragments.

The earlier one enters the market, the more unknowns there are, and the riskier the move. For example, Amazon had to prove people would buy online. Shopify had to prove small businesses could sell online. (They already knew consumers would buy.) New online retailers have to pick the right product and market. (They know if they source the right product and find the right customers, they will buy.)

The risk-reward paradox holds true here. Value accrues to those taking the most risk and so the earliest entrants should be the most valuable.

eCommerce provides a stark example. First entrants are an order of magnitude more valuable than infrastructure players. Infrastructure players are an order of magnitude more valuable than second movers. (Note, chart below uses a logarithmic scale!)

VCs can generate great returns investing across each of these phases. We see this over and over as new markets and technologies emerge. eCommerce and SaaS might be late in their fragmentation cycles but IoT, electric vehicles, blockchain are still ramping. Today, we see startups positioning themselves to be first movers in the new worlds of fitness, education, and other markets fragmenting due to COVID effects. We’ll see capital flow, enabling fragmentation and growth.

Of course, making investments is only one side of the equation. In most cases, markets need to consolidate for exits to happen. The next post will cover consolidation.