The dry powder fallacy: why there is 50% less startup capital than we think

Startup fundraising will hit five-year lows in 2023

If there were any doubt startups would experience a tumultuous 2023, the SVB crisis quashed it. Even though we are on the other side of it, many questions remain. The majority of which, though, can summarize as, "What capital is available?"

To answer that, we must look at the whole ecosystem that creates liquidity.

Supply[startup capital] = VC + NTI + VDVC = venture capital availableNTI - non-traditional investor participationVD = Venture debt issued

We should consider these components individually and together. As both VD and NTI are somewhat dependent on VC. More on this below.

First, venture capital

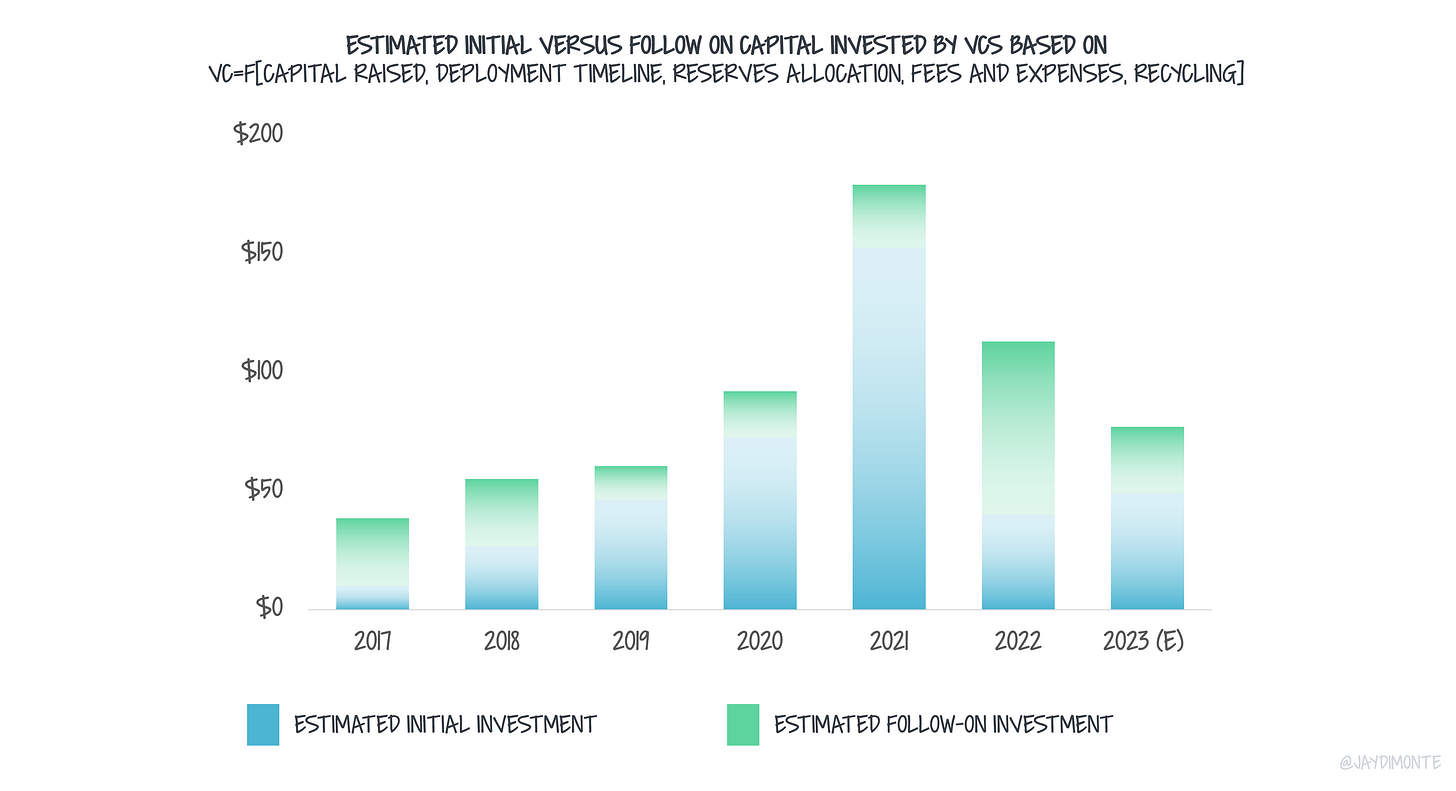

VCs raise capital, consume some of it as fees, and invest the rest over a period of time. Thus, the capital available to startups from VCs in a rather simple function:

VC=f[capital raised, deployment timeline, reserves allocation, fees and expenses, recycling] For example, consider a firm that raises $100M. With 2% of fees set aside, they have $80M of cash to deploy. They make initial investments over a 2-year period and reserve 30% of capital for follow-on. This firm would contribute $80M x (1/2) x (1-30%) = $28M to venture capital supply in their first year of investing.

If that firm instead makes initial investments over a 3-year period and reserves 45% for follow-on, they would contribute only $80M x (1/3) x (1-45%) = $15M to the ecosystem. A 50% increase in deployment timeline and reserves cut 40% of capital deployed in year 1. In this case, a difference of over $10M.

Extrapolated across the few thousand active funds, changes in fund strategy create wild swings in overall market liquidity.

We saw market-driving forces influence funds' investing behavior in 2020-2022. Capital was easier to raise and so VCs did. A prerequisite to raising more capital was investing what you had, so that went faster too. Deployment periods shrunk.

Furthermore, when follow-on rounds become competitive, reserves became less meaningful. So, there was a higher emphasis on initial investment dollars.

To estimate what VCs will invest in 2023, we need to approximate the inputs to the VC formula above:

Deployment timeline - five years ago, VCs raised new funds every 3 years. More recently, VCs were raising every 2. I expect a reversal back to 3-year deployment timelines

Reserves - between a greater opportunity to continue investing in great companies and the need to support struggling ones, I expect reserves to increase by 30-50% over the next year

Capital raised - in 2021-22 VCs raised more capital than ever before. (VCs deployed it faster, too.) I expect fundraising in 2023 to look more like 3-6 years ago than the last 3. Institutional investors, who invest large volumes into VCs, are pausing or reducing commitments

Fees and expenses and recycling - I did not make any assumptions for changes in these variables

In addition to the above, I created a waterfall based on venture overhang. Venture overhang is a measure of dry powder (capital available raised in prior years). All data came from reports published by pitchbook.

All in all, I predict VCs will invest 33% less capital than they did last year.

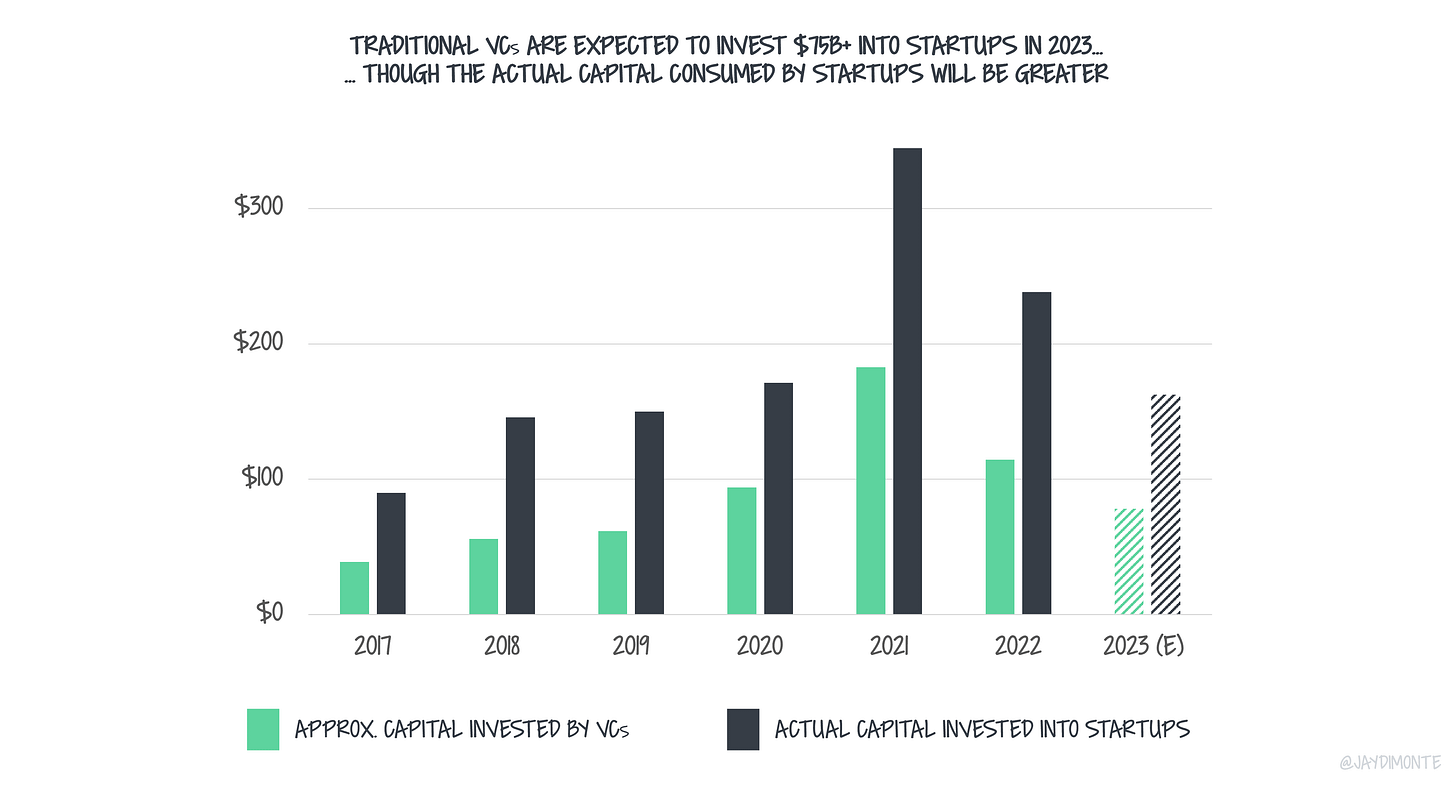

Of course, it is not only VCs that invest in startups. For example, last year, I expect VCs only invested ~$115B of the $344B invested in startups.

I've included a chart to illustrate the point:

The difference is capital coming from non-traditional investors that invest in startups.

Second, non-traditional investors

Non-traditional investors include entities like corporations, hedge funds, and sovereign wealth funds.

NTIs are smaller players in the startup ecosystem on a deal-number basis but invest a lot of capital. Part of this is because they skew later stage (fewer deals but larger rounds). Part of this is because they lead a minority of the time.

The chart below compares deal volume and deal value, and NTI’s role in the ecosystem:

Again, 2021 is an outlier year. 2022 to some extent, too. 2023 will be very different.

Corporates will continue their investments albeit at reduced rates and check sizes. As the majority of these investors tend to follow versus lead, this pullback correlates with the VC market.

After being responsible for a big part of the COVID runup, crossover and other funds will fade. Tiger, being the most (in)famous, has already pulled back. In part because there are other investment opportunities... and in part because their 2021 investments don't look too hot.

The exception here will be roll-ups and re-caps of VC-backed companies.

The sentiment is already showing up in the data. NTI volumes dropped back to 2017-2020 levels over the last year. In continued weakness, NTIs will exasperate capital supply reductions.

Third, venture debt

The other place startups go for capital is debt providers.

In many ways, venture debt markets are dependent on equity markets.

Venture debt is typically no more than 30% of venture capital invested in any round. E.g. a $10M Series A could come with a $3M debt issuance

Venture debt sits senior to equity. in some ways, debt is a bet that equity supports the company. The next equity raise provides enough capital supply to cover any outstanding debts. Weaker VC markets dampen VD outlooks.

As the venture capital market pulls back, so too will the venture debt. For example, I expect a reduction of 10% in VC deployed also correlates with a ~10% pullback in VD.

We see this in the data; VD is typically 15% of total capital accessed by startups.

Again, the exception is 2021 when VC was flowing (and in many ways “less expensive” than debt).

In addition to a reduction in equity investment, two major factors will change the VD market in 2023.

Decreased demand due to interest rates: Interest rates are the biggest determinant of the price of debt. Other covenants, like warrants, can make debt more expensive as well. As price increases, demand decreases. However, the cost of equity has also gone up, which might make the more expensive debt more palatable.

Decreased supply due to SVB, Signature, and pressure on Regional Banks:

First, SVB was about half of the venture debt market. Though Even with the acquisition by First Citizens Bank, we don’t know what portion of that debt supply will remain accessible. Let’s say 30-50% of SVB’s debt supply evaporates. That would decrease the overall debt supply by 15-25%.

Second, the bar for issuing debt will inevitably rise. Startups are becoming riskier at the same time that safer assets are producing yield.

Third, deposits are down. (1) Startups’ balance sheets shrink as they continue to burn capital. (2) Startups diversified deposits across various banks, many of which do not provide venture debt. Let’s assume between this and the former point, we shave another 10-25% off the overall debt supply.

Over the last four years, debt providers infused $31-35B into the startup ecosystem. Between market pullbacks and decreases in supply and demand, I expect this number to drop closer to $15-20B.

Finally, what will startup capital supply look like in 2023?

Let’s acknowledge one big assumption, which I am 95% confident is true. Capital supply will be the constraint this year, not demand.

Accordingly, We can approximate what capital startups will consume in 2023. It will be equal to what is available from VCs, NTIs, and VD.

The activity in Q1-2021 through Q2-2022 was an anomaly and one that we may not see again for another decade (if ever). It’s looking like the good times of 2018-2020 may be optimistic as well.

I expect in 2023, the capital available to startups will be at its lowest level since 2017.

What does this all mean?

Startups that want to raise capital will not or will raise less than they intended. Last year's $10M Series A will be this year's $5M. Prices will adjust accordingly.

Pacing for new investments continues to slow. Attention and momentum become more important fundraising easily drags in this environment. Days- or weeks- long diligence periods extend to months.

Companies will fail to raise. As these stories come out, power will continue to shift to capital providers.

There will be a dramatic “flight to quality” as more capital chases fewer companies. Strong will pull further ahead as their resource availability (capital, talent, mindshare) increases. This will be acutely felt at the later stages.

The seed stage will look more attractive. There’s little capital stack to overcome or prior pricing that feels outdated. Both seed funds and multi-stage funds will be active at the early stage.

We have not yet hit steady-state and will not until we work through the aftermath that came about in 2021-22. Unfortunately, the transition from surplus to scarcity is painful.

It is difficult to avoid complete pessimism but we should. Few companies are up-and-to-the-right 100% of the time. We expect bumps along the road. Two years ago, it was difficult to attract talent. Today, it's capital.

Where abundance breeds exuberance, austerity breeds durability.

Durable companies will win in this market.