Unlocking hidden value: How niche markets are bigger opportunities than VCs think

Ode to Procore; a case study on niche versus mass-market project management software

The easiest way for a VC to kill a deal is to state “The market is too small.”

I happen to think this is the laziest way as well.

Part 1: Why good segmentation matters for big and small markets

It takes work to segment markets.

When market sizing becomes a perfunctory exercise, it can lead to errors.

VCs give horizontal markets, the “mass market,” the benefit of the doubt. If you can sell to everyone, the potential is limitless. We don't need to measure how big these markets are because they are huge.

Consider project management software for teams. Teams! They are everywhere!

But not all teams are the same. Some may have the power to buy software using their credit card. Others may need IT or VP approval. Some may be agile. Others may be lean. Some are distributed. Others huddle around whiteboards. One project management solution might be right for some but not others. Assuming all these teams are in our market is incorrect; we have not segmented customers.

Industrial markets are not allowed this same benefit of the doubt. Often underestimated, rarely overestimated.

Consider project management software for construction. More specifically, General Contractors. How about the mid-market? We need to do the math here. If you squint, yes, it's "big enough." But is it exciting? I don't know. VCs get stuck here. It's easy to ignore the growth potential that starts with dominating a "niche."

Market definition starts with the right segmentation

Compare the process for understanding the potential for mass-market vs. industrial markets. We "feel" that mass-market opportunities are big enough. We "calculate" industrial market sizes.

Instead, every company should go through the same market definition process. This is good for market sizing. It is better for informing what product to build and how to sell it.

To define a market, identify: Who has the pain that I am trying to solve? Are they capable of adopting my solution*? Are they able to buy it (based on how I am selling)?

*This is more important in some markets than others. For example, customers in industrial markets have different resources (people and systems) that impact their ability to adopt software. For example, you need clean data before you can run analytics.

A customer segment needs to have three common attributes: same problem, solved in the same way, with the same buying behavior.

Our target market includes everyone who exhibits these three behaviors. It excludes anyone who only exhibits one or two.

Once we understand who falls into and out of that bucket, then we should look for common demographics. These demographics allow us to market size. They also help us identify and target potential customers.

Initial target markets should be small

Any initial market should be well-defined. It might also feel too small. That's ok, it’s likely smaller than the eventual opportunity.

For example, consider a solution that helps freight carriers process orders.

Who has this problem? Anyone with an overload of email bogging coordinators down → All carriers

Can it be solved in the same way? Anyone who does not need IT to get involved with integrations --> All carriers + without a TMS (transportation management solution) and small (or no) IT department

Do they buy similarly? Anyone who buys software on a credit card and attends industry conferences --> All carriers + without a TMS and a small (or no) IT department + with less than 250 trucks

This is a great initial market because it is well-defined and easy to identify. We can learn a lot by experimenting with these customers.

This is not our eventual market though. Many VCs get stuck thinking it is. In that case, it might be too small.

What we need to do is look at what happens when we remove one of these constraints. How hard is it to service the new customer segment?

For example, remove the implementation constraint. If we add the ability to integrate our product into existing systems, we can sell to carriers with a TMS. It might not be that much work to make that happen either.

We should consider every vector for market growth and how natural it is to pursue them. Markets can get big when you do it.

Part 2: Where small markets have advantages

Often the upside of pursuing a niche market outweighs the downside. Especially when you can dominate that market.

Potential downside:

The market segment we chose is too small and we get stuck. This limits growth trajectory and exit potential

Potential upside:

Opportunity to find better product-market-fit and build a niche monopoly

Once established, the opportunity to play offense versus defense

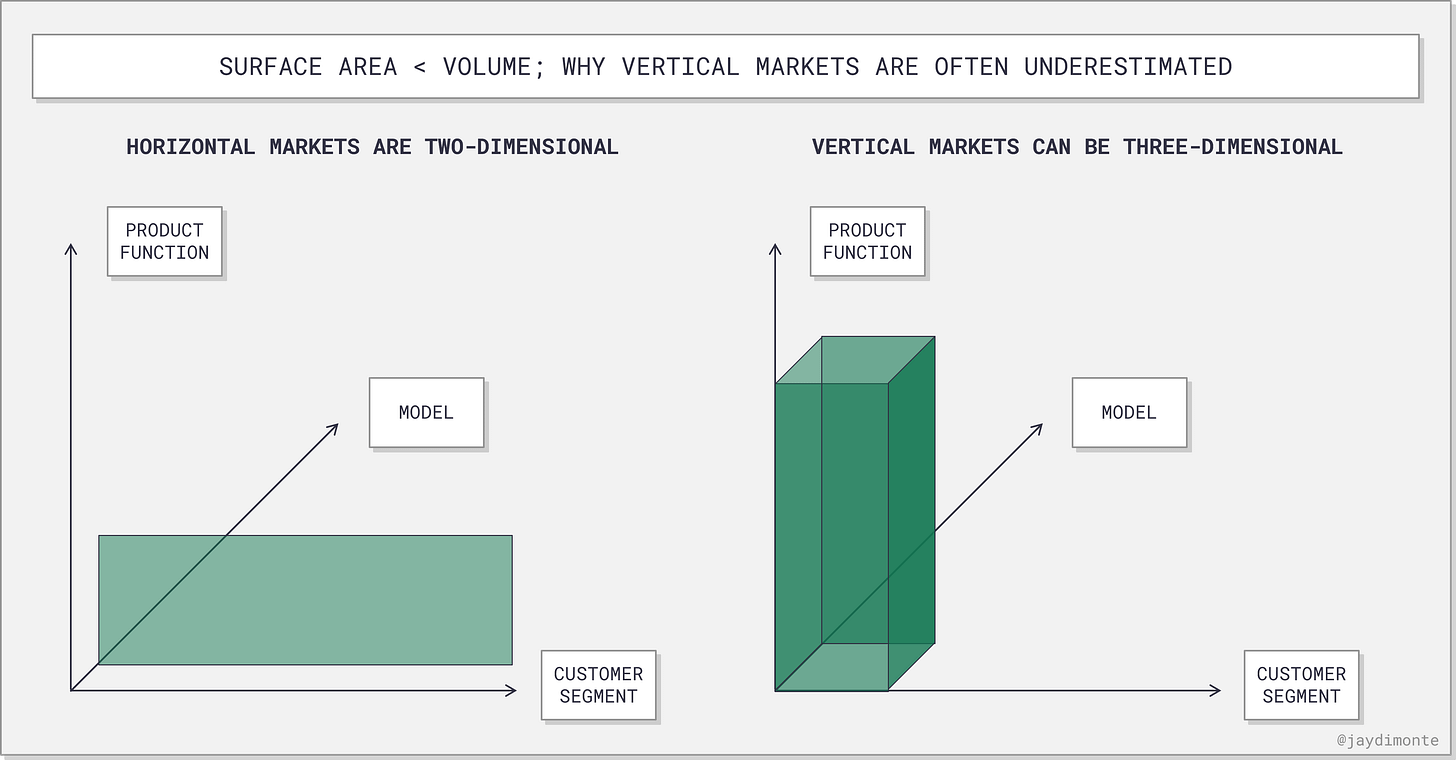

Opportunity to expand in 3D versus 2D

Niche monopolies come from better PMF

The first here should be obvious. When a product is purpose-built for a customer, it is more likely to “check the box” on all product requirements than on just a few of them.

Niche monopolies play offenses versus defense

When this relationship is established, the threat of competition also goes down.

The better you are at serving your customers, the less likely they are to leave you. The willingness to buy more from you, their trusted advisor and partner, goes up. This allows for more moves on "offense."

Mass-market vendors may not have this same opportunity. These companies weigh tradeoffs between new feature sets, customer requests, and value creation. In doing so, some customers are much better served by others. This leaves vendors exposed to niche providers that target those under-served customers. This is not as strong of a foundation for partnership and requires more "defense."

Niche monopolies expand in 3D

A byproduct of big markets is no need to add customer segments or business models. This keeps mass-market startups them playing on a 2D field. Many customer types but only one core product function, and one business model.

Niche markets use their monopoly platform to expand in 3D. When you are a partner versus a vendor, when customers spend the majority of their time in your app, you have an advantage. Finding ways to add more and capture more value is easy. You may add products that introduce new models (marketplace, fintech, etc.).

This is a transition made over time. At the seed stage, focusing on one customer, one product, and one model is typical. At Series A, we may have expanded in one direction. But at scale, that is when we see expansion in a few dimensions.

Part 3: For example, Procore & Other project management SaaS

There are great examples of this 2D vs. 3D model at scale.

Procore is a prime one in the industrial space.

Consider this slide from Procore’s 2022 Investor Day Presentation. At seed, one customer, one product, one model. Now three customers, a platform, and many revenue segments.

However, project management software companies serving the mass market have not managed this 3D growth.

To illustrate, I will compare Procore to Asana, Monday.com, and Smartsheet, the “Project Management Trio.”

These companies are all public, independent, and are high performers on G2’s magic quadrant… comparable to Procore.

The performance of these companies is comparable as well. All were venture-backed but are public now. Growing but still unprofitable.

These similarities in product, stage, and scale make precise comparisons possible.

To illustrate the difference between Procore's 3D expansion and the PM Trio's 2D expansion, we must consider their strategy yesterday, today and tomorrow.

I do this by comparing (1) acquisitions made (2) customer focus in 2024 based on annual reports and (3) product goals in 2024 also based on annual reports.

1. Acquisition Strategy: Procore expands, PM Trio doubles down

Procore and Smartsheet have each made a handful of acquisitions. Acquisitions inform strategic priorities. (Neither Asana nor Monday.com have announced any.)

Procore’s acquisitions drove market expansion. Some enabled additional offerings to newer customer segments (owners and specialty contractors). Others also added business models (transactions).

Smartsheet's acquisitions all seemed to supplement the core project management platform.

2: Customer Focus for 2024: Procore expands, PM Trio doubles down

Procore's niche beginnings are evident in its customer base. They have the greatest concentration of enterprise customers ($100K+ ARR), of customers in the US, and of a single market segment (majority of revenue from GCs, 100% from construction). Their expansion avenues are evident as well. Their focus in 2024 is growing internationally and within new customer segments (owners and specialty contractors).

The mass-market nature of the PM Trio is also clear. Their customer bases' span sizes, segments, and geographies. Their focus is slightly narrowing over time; all three stated a focus on "the enterprise" in 2024.

You may think Procore is adding market segments because they saturated the GC market. That's not true. Only 2% of Procore's potential US customers are actually customers. (They are large customers though, managing ~12% of construction volume.)

On the other hand, the PM trio boasts market capture of enterprises already. Smartsheet works with 85% of the F500. Monday, 59%. Asana, 48% of the Global2000. This implies saturation in the project management market. It also demonstrates a market that lacks real moats and monopoly potential.

(Note, this does not have a meaningful impact on customer retention or expansion. All companies have net revenue retention between 110-120% for core customers.)

3. Product and model focus in 2024: A diverse set of priorities

Procore has big plans for 2024. The company is continuing its pursuit of materials financing and early pay/factoring. Additionally, the company is making a push into insurance. This includes two new products/revenue streams. They will serve as a broker (transaction) and partner with underwriters (data product). These are distinct from their SaaS model and app marketplace.

The PM Trio is less diversified. Asana is making a push into AI with their copilot product. Monday is releasing its database product which allows for improved performance at scale. Both attempt to make the core product more useful, provide more value, and perform better. Neither opens up net new revenue streams or markets.

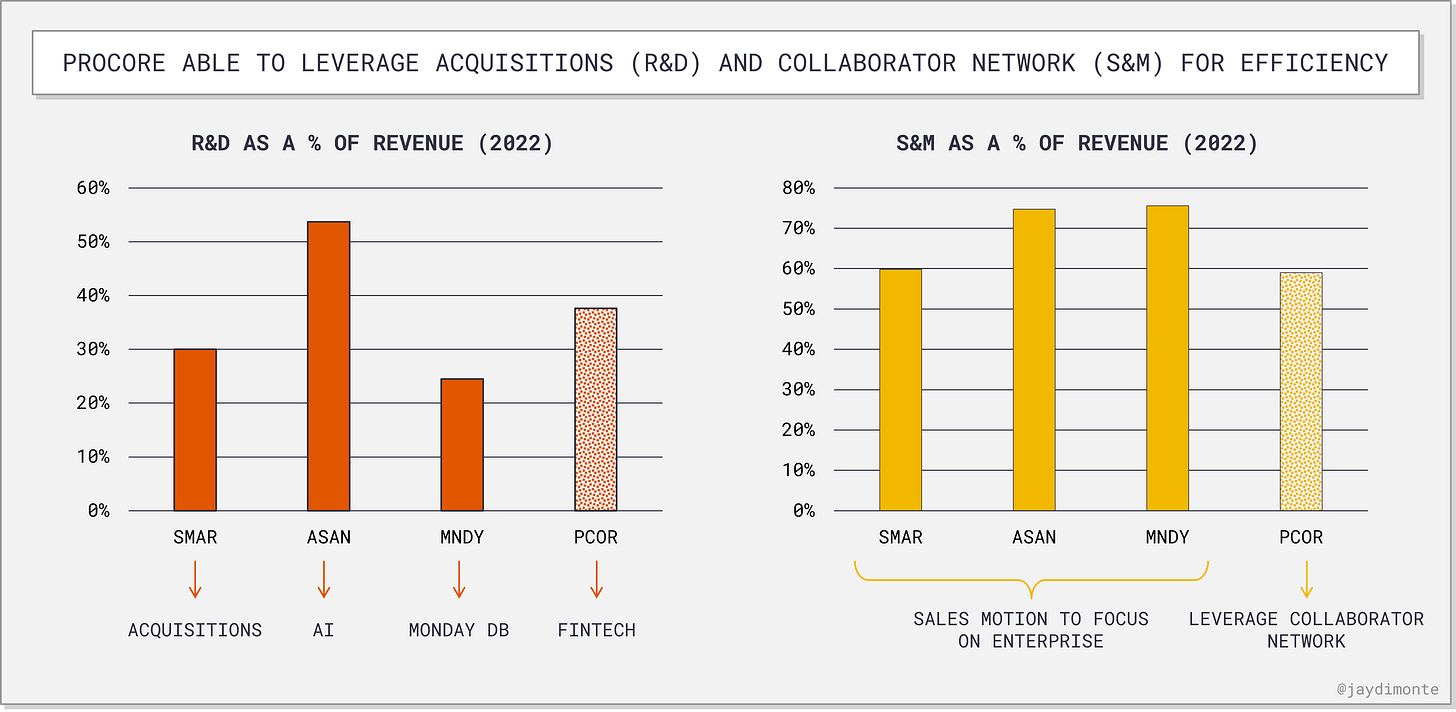

Company investments correspond to strategic priorities

Procore is investing heavily in developing new products. Makes sense, given its big aspirations.

Even so, the percentage of revenue Procore spends on R&D (38%) is close to the average R&D spend by the PM Trip (36%). Procore has strong relationships with core customers. Its customer problems are analogous. Presumably, it makes Procore's product development more effective and efficient despite its scope.

Procore spent the least on S&M as a percentage of revenue. They have 16K customers who introduced 520K collaborators to the product. Presumably, this makes for more efficient sales... 40% of new logos last year were collaborators.

Asana and Monday are investing in S&M. Enterprise sales is not a low-touch, low-effort endeavor.

Though in the same place today, Procore and the PM Trio started in different spots: A VC miss?

Procore’s performance is similar to the PM Trio today: great. In FY 2023, the PM Trio’s average revenue was $680M, growing 40% YoY. Last year, Procore’s revenue was $720M and grew 40%.

Procore’s progress was similar to the PM Trio while reaching scale. The year before Procore reached $100M in revenue, they had raised $180M in venture capital. For Monday, that was $234M. Asana, $213M. Smartsheet, $121M.

However, Procore’s beginnings were very different. Procore’s first $5M+ round was a $16M round led by Bessemer in 2014, 12 years after the company launched. Smartsheet, a $26M round led by Insight and Madrona seven years after founding. Monday, a $7.6M round led by Entree Capital, five years. Asana, $9M round led by Benchmark one year after.

It took Procore much longer to get “venture ready” than the PM Trio. (Some credit this to the adoption of mobile fueling Procore adoption, others on the contrarian nature of constructions SaaS.) However, once it got there… it performed as well as if not better than mass-market equivalents.

Net, companies targeting niche markets are capable of exceptional performance and scale. And they have many vectors to pursue additional scale.

Part 4: Thoughts on building niche monopolies

Procore is an aspirational but cautionary tale for seed companies and investors.

Today, it is exceptional. It continues to push the limits on market expansion when its peers are trying to define theirs.

But, it took a long time to get here. Mobile seems to be an unlock. But so did access to capital and resources. Would raising VC earlier accelerate its growth? Were VCs right or wrong to wait?

This might be a moot point today. I am excited that industrial markets are adopting tech faster today than ever before. Urgent demand for resiliency, efficiency, and growth means the next Procore is advantaged.

Even so, these markets lack early adopters (I wrote more on that here). Early-stage startups need to do three things if they wish to avoid Procore’s early years of purgatory.

Dominate core market segment and product fast

Identify possible product, customer segment, or model expansions.

Demonstrate that these expansions are possible, efficient, and natural extensions of the core

To raise a Seed round, founders should identify strategy behind #1 and #2

To raise a Series A, founders should make progress on #1 and #2, and identify the strategy for #3

Thereafter, it is important to show that the market opportunity is theirs for the taking.

At the same time, founders and their investors must regularly check their assumptions on #2 and #3. Are these growth vectors feasible? Are they exciting? Do they mean the opportunity looks more like Procore or LevelSet or LaborCharts? Capital raised must match market potential.

I for one am excited about more and more of these opportunities.

We have the market. We have the playbooks.

Let’s build the next Procore.

What an insightful way of looking at the topic. Great work, Jackie!

great post!